By Karin (Catharina) van den Driesche, KADEN DESIGN and University of Amsterdam

I’m happy to share that recent collaborative research with Åsa Cajander and Shweta Premanandan (Department of Information Technology, Uppsala University) will appear in an upcoming Springer volume on Academic and Professional Practice in Interaction Design. The work grew out of two Biomimicry for HCI workshops held at Uppsala University exploring how nature can inform future forms of interaction beyond screen design. The paper was also presented at the Academic Research and Professional Practice in Interaction Design (ARPIDD) conference in London (10–11 July 2025), where researchers and practitioners exchange perspectives on design, technology, and professional practice.

In this blog post, I want to reflect on what the paper Biomimicry: A Transdisciplinary Approach for Human Computer Interaction means in practice: what happens when designers begin to integrate inspiration from living systems, where the workshop participants encounter friction and surprise, and why these matters for how we design technologies in a time of ecological uncertainty.

Exploring Biomimicry in Interaction Design Practice

Biomimicry, learning from nature’s strategies and processes, has long been applied in fields such as architecture, materials science, and engineering. In interaction design, however, its potential is only beginning to unfold. As interfaces move away from screen displays toward spatial, embodied and sensor-rich environments (i.e., scene-based design), designers increasingly need new ways of thinking about perception, adaptation, responsibility, and long-term impact.

At the same time, HCI does not exist in isolation from global challenges. Climate change, biodiversity loss, and resource pressures call for design approaches that move beyond purely human-centered perspectives. Interaction design increasingly needs to acknowledge nonhuman needs, ecological impacts, and long-term systemic consequences.

Biomimicry offers a way to bridge these challenges. By studying how living systems regulate, adapt, cooperate, sense, and evolve, designers can translate biological strategies into interaction principles that support resilience, sustainability, and regenerative thinking.

Biomimicry for HCI workshops

The Biomimicry for HCI workshops invited participants to experience biomimicry as a way of thinking and relating to strategies found in nature. Participants moved between learning biomimicry principles, abstracting biological strategies, and transposing those insights into speculative interaction scenarios. These scenarios helped move the focus away from surface resemblance toward deeper structural understanding, how systems adapt, how information flows, how materials respond, and how organisms coordinate with their environment over time.

Importantly, this way of working opened new perspectives on the role of nature in the design process. For some participants, nature became something to observe closely, learn how nature offers solutions. For others, nature functioned more indirectly, guiding the way problems can be re-framed and how consequences were anticipated. In both cases, the scenarios extended towards scene-based interactions that could benefit both human and nonhuman environments.

What I found particularly valuable was how the workshops created space for dialogue across disciplines and experiences. This distributed way of working mirrors the interconnectedness found in ecological systems themselves, reinforcing the idea that meaningful innovation rarely emerges from isolated perspectives.

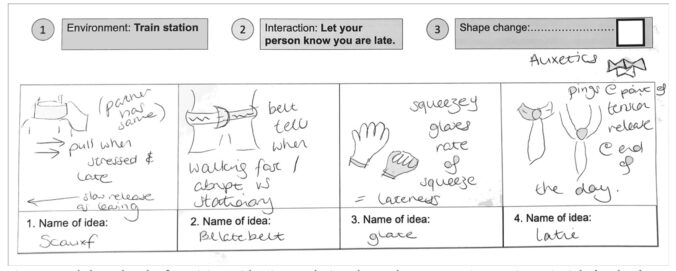

The illustration for the blog post shows a workshop sketch of participant ideation exploring shape change as an interaction principle (author’s own material).

Adopting biomimicry as a design practice therefore benefits from cross-sector collaboration between academia, industry, and societal actors. Its value lies not only in generating new concepts, but in cultivating a way of working that aligns technological imagination with ecological responsibility, long-term thinking, and relational awareness.

Nature’s New Possibilities for HCI

Nature rarely offers neat or isolated answers, it operates through layered relationships, long timescales, and continuous interaction with its environment and relational context. One of the notable aspects of the workshops was not the ideas themselves, but the cognitive effort participants experienced while working with biological principles. Abstracting and transposing living systems into interaction concepts requires stepping away from familiar design habits. Bringing that analogical mindset into design thinking takes practice.

At the same time, moments of clarity emerged when participants began focusing on structural relationships rather than appearances: how shapes distribute information, how materials respond to pressure, how feedback loops stabilize or transform behavior. These moments often unlocked grounded ideas, helping participants bridge biological insight with technological imagination without losing integrity along the way.

Another aspect became visible between ecological ambition and practical constraints. Designers wrestled with questions of feasibility, cost, accessibility, and technical maturity. How can a nature-inspired idea remain meaningful when translated into scalable systems? How do we avoid creating concepts that sound visionary but cannot responsibly be implemented?

What this revealed is that biomimicry is not a shortcut to innovation, it is a discipline of analogical thinking. It demands careful observation, critical interpretation, and collaborative sense-making across domains. It also calls for design education and professional practice to cultivate stronger analogical thinking skills, ecological literacy, and long-term responsibility.

What became clear during the workshops is that biomimicry doesn’t replace existing HCI methods, it adds another way of thinking. It offers structure, but also leaves room for exploration, helping designers engage more deeply with biological principles.

For me, this is where biomimicry becomes more than a method. It becomes a way of slowing down design enough to notice what kinds of relationships we are creating between humans, technologies, and the natural world.

Explore the Biomimicry Method Yourself

If you would like to experiment with biomimicry in your own teaching, research, or design practice you can download the worksheet: Biomimicry using Nature’s Shape Change for Interaction Design. This worksheet supports abstraction, analogical translation, and scenario development, and can be used in education, co-creation workshops, and early-stage concept development.

- Download the worksheet Biomimicry using Nature’s Shape Change for Interaction Design (PDF): https://kadendesign.nl/images/KD_Worksheet_Biomimicry_Shapechange_June2024.pdf

If you’re interested, you can find (March 2026) the paper “Biomimicry: A Transdisciplinary Approach for Human Computer Interaction” here: DOI:10.1007/978-3-032-15516-0_3.

The publication contributes to ongoing conversations within HCI, design research, and organizational studies about how technology can be shaped in generative ways that respect both human and nature. Importantly, the paper also explores how biomimicry can be aligned with industry roadmaps and organizational strategies, helping companies develop responsible innovation pathways while reducing unintended ecological consequences. This creates space for new forms of collaboration between researchers, designers, communities, engineers, and domain experts.

For collaborations and exploring ideas in Biomimicry for HCI, please reach out to me at c.j.h.m.vandendriesche@uva.nl or info@kadendesign.nl.

Karin van den Driesche