Det jobbigaste i arbetsmiljön är väl egentligen när det är dåligt väder.

– Lastare på stor svensk flygplats.

Det finns vissa saker som kommer tillbaka årligen i svensk medial diskussion. Melodifestivalen i all ära, men framförallt återkommer diskussioner kring den eviga kampen mot snön och hur det kan komma sig att snön påverkar vår trafik så pass mycket som den gör i vårt land. Nu i början av nådens år 2026 manifesterades detta fenomen inte minst på landets flygplatser, inte minst på Arlanda, och inte minst på bagagehanteringen. Ena kanalen efter den andra rapporterar om kaoset [1,2] och opinionstexter skrivs för att peka på problemet [3].

Givet att mitt främsta forskningsprojekt har varit med fokus på just markarbete på flygplatser och hur tekniken påverkar deras arbete, och speciellt eftersom väderförhållanden har varit ett återkommande ämne i vårt projekt, vill jag nyansera bilden lite och ge mina topp 5 komplimenterande perspektiv till varför vädret kan ha påverkat denna gång (och kan komma att göra i framtiden). Det ska sägas att det här är inte ett exakt facit kring varför det blev så denna gång och att det inte är något en specifik person på Arlanda har sagt om just denna situation, utan mina bedömningar gällande vad som mycket väl kan ha påverkat.

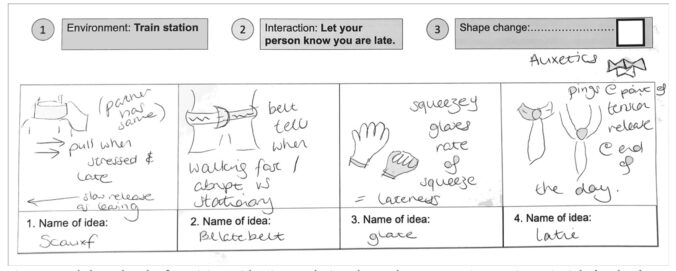

- Fundamental teknik blir långsammare. Bagaget lastas in i flygplanet med hjälp av så kallade lastband. På grund av hur de är konstruerade blir det segare i kyla, adderar stress och kan göra arbetet långsammare. Överlag hjälper dessa hjälpmedel mycket med arbetet och den fysiska arbetsmiljön. Det är mycket bättre att använda dem än att lasta från marken, så att inte ha det för att det blir svårare i snö är inte ett argument.

- Jobba med skärmar är svårt i snöstorm. Många flygbolag kräver idag att bagage scannas innan det lastas. Säkerhet och möjligheten att underlätta att hitta bagage som ska plockas bort om någon inte dyker upp är återkommande argument för detta. Att använda skärmteknik i snö med allt krångel det kan komma med kan mycket väl bidra till extra försiktighetsåtgärder och behov att dubbelkolla att scanningen har genomförts på ett korrekt sätt.

- Många roller ska samsas på liten yta. Mat, avlopp, tankning: alla roller har sina utmaningar med vädret. En tankare beskrev det en gång som att de skulle kunna kvalificera sig till curling VM givet hur mycket snö de behöver skotta för att få tag på brunnarna med bränsle. Snön försvårar för flera och kan påverka koordinationen mellan roller och smidigheten i processen som helhet.

- Bagagevagnarna väger flera hundra kilo, speciellt med all skidutrustning och allt vad folk kan tänkas behöva ha med i sina vinterresor. Lägg till snö och behovet att justera dem för hand lite då och då. Tyngre, jobbigare, långsammare i snön.

- I slutändan handlar allt om säkerhet, flygplatsernas modus operandi. Verksamheten kräver försiktighet överlag. Teknik som krånglar kan skapa osäkerhet för personal, resenärer och utrustning, speciellt i svåra väderförhållanden. Säkerheten blir därmed extra viktig.

En beskrivning av industrin jag gillar är att flygplatserna jobbar med ”minutlogistik” – och med vädret som det kan vara här i norr leder det till lager på lager av försvåringar – vilket påverkar hanteringen minut efter minut. Allt som allt adderar detta stress till system och människor, vilket kan leda till att aktioner tar längre tid.

När teknik utvecklas bör alltså inte kontexten (och vädret) glömmas bort och alltid vara i riskanalysen och kravspecifikationerna. Förseningar som vädret är med och bidrar till kan inte endast tillskrivas denna eviga boven i dramat ”den mänskliga faktorn”. Framför allt är bagagehantering en mycket mer komplex arbetsuppgift än vad man kan tro, och kräver långt mycket mer än endast en bagagevagn.

“The toughest part of the work environment is really when the weather is bad.”

– Ground handler at a major Swedish airport.

There are certain things that return annually in Swedish media discussions. Melodifestivalen by all means, but above all, the recurring debates about the eternal struggle against snow and how it’s possible that snow affects our traffic as much as it does in this country. Now, at the beginning of 2026, this phenomenon manifested itself at the nation’s airports, especially at Arlanda, particularly within baggage handling. One media channel after another reports on the chaos [1,2], and opinion pieces attempts to point out the root of the problem [3].

Given that my main research project has focused specifically on ground operations at airports and how technology affects their work, and especially since weather conditions have been a recurring topic in our project, I want to add some nuance and offer my top five complementary perspectives on why the weather may have caused issues this time (and may continue to do so in the future). It should be said that this is not an exact explanation of why things happened as they did in this particular case, nor is it something any specific person at Arlanda has said about the situation. Rather these are my assessments of what could very well have contributed.

- Fundamental technology becomes slower. Baggage is loaded into the aircraft using so‑called belt loaders. Due to how they are constructed, they become sluggish in the cold, which adds stress, and can slow down the workflow. Overall, these tools greatly support the work and physical work environment. They are far better than loading straight from the ground, so not using them because they become more difficult in snow is not a viable argument.

- Working with screens is difficult in a snowstorm. Many airlines now require baggage to be scanned before loading. Safety and the ability to locate baggage that needs to be removed if a passenger doesn’t show up are recurring reasons for this. Using screen‑based technology in snow – with all the complications that come with it – can easily lead to extra precautions and the need to double-check that the scanning has been done correctly.

- Many roles have to share a small space. Catering, sewage, fueling – every role has its own challenges in bad weather. A refueler once described that they could probably qualify for the curling world championship given how much snow they have to clear just to reach the fuel pits. Snow complicates things for many roles and can impact coordination and overall workflow.

- Baggage carts weigh several hundred kilos, especially with all the ski equipment and whatever else people need to bring on winter trips. Add snow, and the occasional need to manually adjust or realign the carts. Heavier, tougher, slower in the snow.

- In the end, everything comes down to safety, the airport’s modus operandi. Operations require caution in general. Technology that malfunctions can create uncertainty for staff, passengers, and equipment, especially in harsh weather conditions. Safety therefore becomes even more critical.

One description of the industry that I like is that airports work with “minute logistics” – and with the kind of weather we get up here in the north, which leads to layer upon layer of complications, the process is affected minute by minute. All in all, this adds stress to both systems and people, which can make tasks take longer.

Therefore, when developing technology, context (and weather) must not be forgotten and should always be part of risk analyses and requirement specifications. Delays that the weather contributes to cannot be attributed solely to that constantly reoccurring villain “the human factor.” Above all, baggage handling is a far more complex task than one might think, requiring much more than just a baggage cart.

References:

[1]: Bagageförseningar på Arlanda i snökaoset | SVT Nyheter